Dr Elizabeth Dearnley, University of London

In her memoir about her role in creating the Cottingley Fairies photographs, published posthumously in 2009, Frances Griffiths recalled her first impressions of a wintry West Yorkshire. Arriving from South Africa in the spring of 1917 to find blacked-out streets and snow still on the ground, nine year-old Frances found that she was to share a bedroom with her older cousin Elsie:

‘[it] was small, with the window only about two feet from the end of the bed. This window had no curtain and the view in the daytime was a very good one; across the beck, up the slope, with a range of hills at the skyline. But it frightened me to death at night. A blank shiny piece of black glass, with nothing beyond but the roaring of water.’[1]

Growing up in Bradford in the 1980s and 90s, I’d always been vaguely aware of the ‘Cottingley Fairies hoax’— that two young girls claimed to have taken photographs of fairies and fooled the creator of Sherlock Holmes into a reputation-ruining endorsement — without thinking too much about the girls themselves.

Posing by the beck with flowers in their hair, the images of Frances and Elsie have become as much a part of the Cottingley mythology as the cut-out paper fairies. However, the best-known accounts of the story are Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1920–21 Strand articles, his 1922 book The Coming of the Fairies, and leading Theosophist Edward Gardner’s 1945 Fairies: The Cottingley Photos and their Sequel, all celebrating this photographic proof that fairies exist. In 1990, paranormal investigator Joe Cooper published The Case of the Cottingley Fairies, a book that he had planned to co-write with the cousins until they fell out. Cooper, a believer in fairy life, never fully recovered from discovering the deception, and his portrait of them is awkwardly skewed and strained as a result. While grainy 80s television interviews exist of the girls as older women revealing how they had staged the pictures with drawings and hatpins, their own voices seemed largely missing from the narrative.

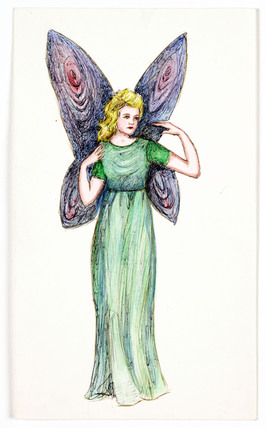

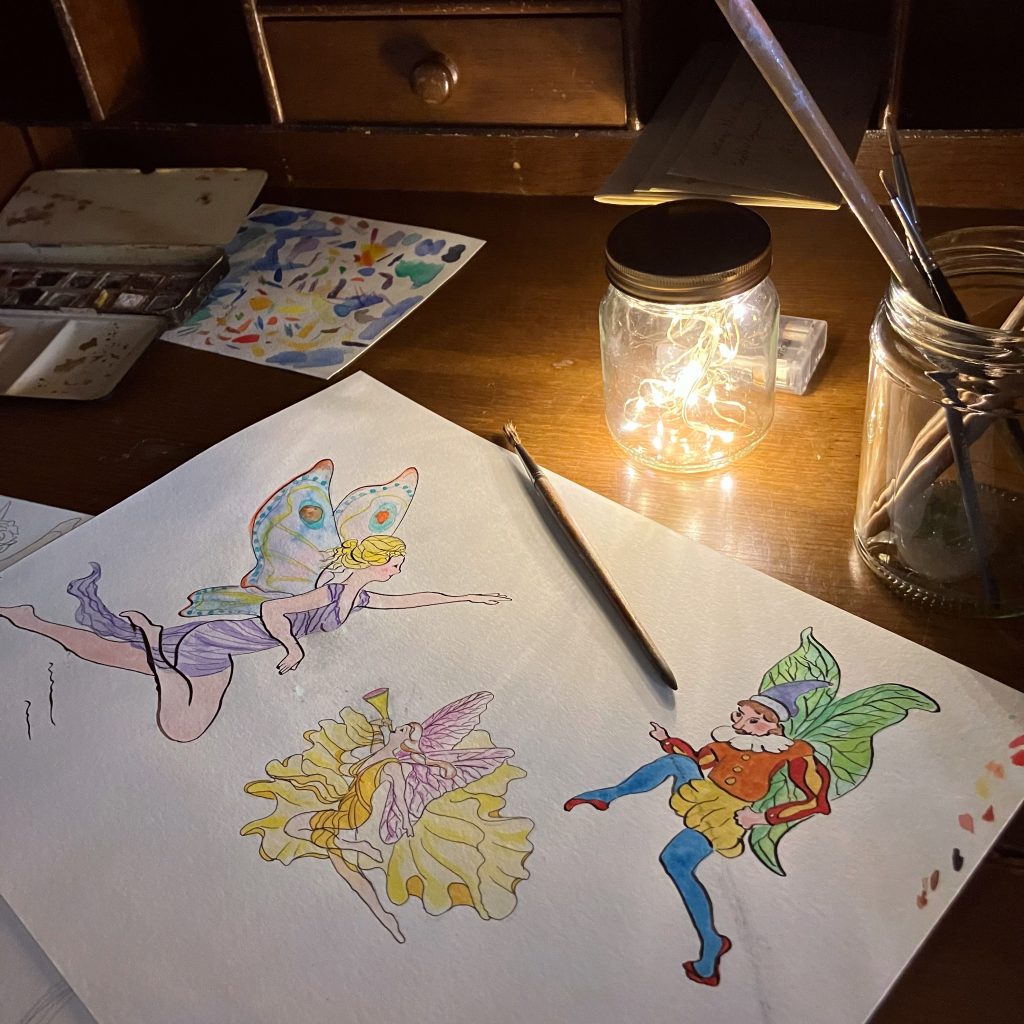

Elsie Hill’s fairy drawings, c. 1983 / © Science Museum Group collection

As a folklorist and installation artist, I wanted to revisit the story from the perspective of the girls themselves in the centenary year of Conan Doyle’s The Coming of the Fairies: what prompted them to take the pictures in the first place, and how did something that started as a family practical joke get so out of hand?

I hadn’t been aware that either had written about the events from their perspective until discovering Frances’s memoir while editing weird fairy fiction collection Fearsome Fairies in 2021 — nor that Frances had maintained for the rest of her life that she genuinely had seen fairies by Cottingley Beck (the cut-outs made by the fun-loving Elsie as an ingenious way to stop the grown-ups laughing at their stories). Frances’s book, Reflections on the Cottingley Fairies, had an extremely small print run and is now almost impossible to buy. But Frances’s own account of the summer of 1917 adds a fascinating additional dimension to the tale, suggesting that the ‘Cottingley hoax’ is a more complex story than it is usually remembered for being.

Working with musician and sound designer Tamsin Dearnley and filmmaker Amy Cutler, I designed Fairy Light, an immersive space in Leeds Central Library staged between 27 May and 8 July 2022 which reimagined the bedroom shared by Frances and Elsie that summer, alongside a dramatised conversation between the cousins accessed via QR code.

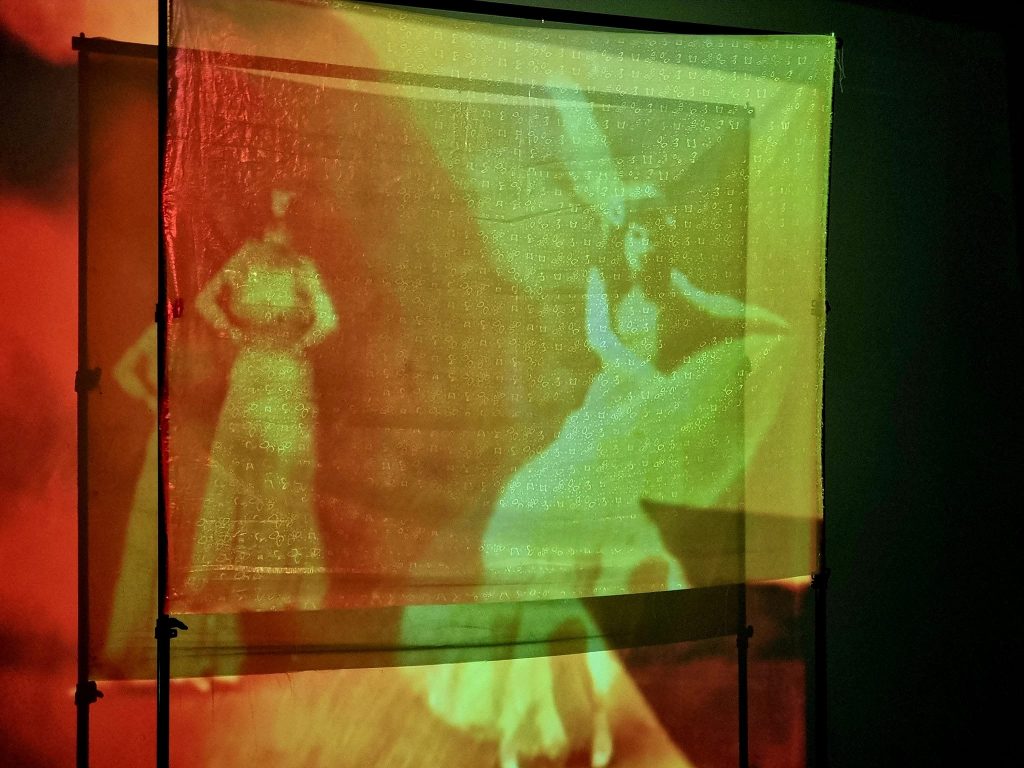

views of the Fairy Light set

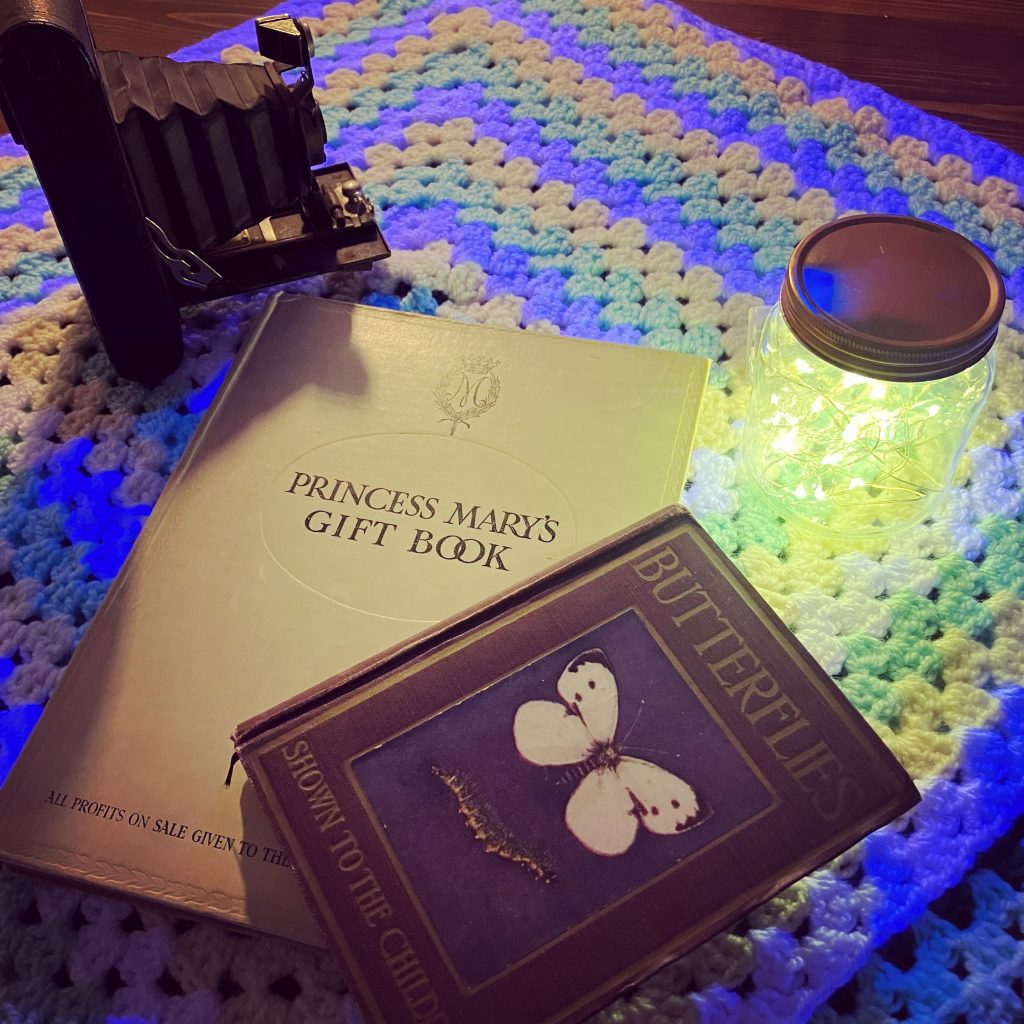

This is the third immersive installation I’ve created which takes place in a childhood bedroom (previously I’ve created 1940s Red Riding Hood-inspired Big Teeth and Hoffmann retelling The Sandman at the Freud Museum London); as a child, I loved stories about portals into other worlds such as Where The Wild Things Are, The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, and I’m fascinated by the way these cosy, ordinary spaces can be transformed in the imagination into something altogether more magical. Taking Frances’ description of lying in bed listening to the roaring of the beck as a starting point, I also included several objects mentioned in her memoir, such as an original copy of Princess Mary’s Gift Book, which Elsie used as the inspiration for her fairy cut-outs, watercolours by ‘Elsie’ (created by Joan Dearnley), and a stone hot water bottle which Frances describes using to ward off the freezing Yorkshire temperatures.

Tamsin created a ‘reactive soundscape’ of eerily enchanting sounds (Cottingley Beck and birdsong recorded on location, harp music supposedly ‘transcribed from the fairies on Dartmoor’ in 1922, popular songs from the First World War, ‘Elsie and Frances’ laughing) which used motion sensors to react to the movement of people in the room: the more movement detected, the more sounds were triggered. In this way, the audience became active participants in the installation, increasing the likelihood that the presence of fairies would be detected.

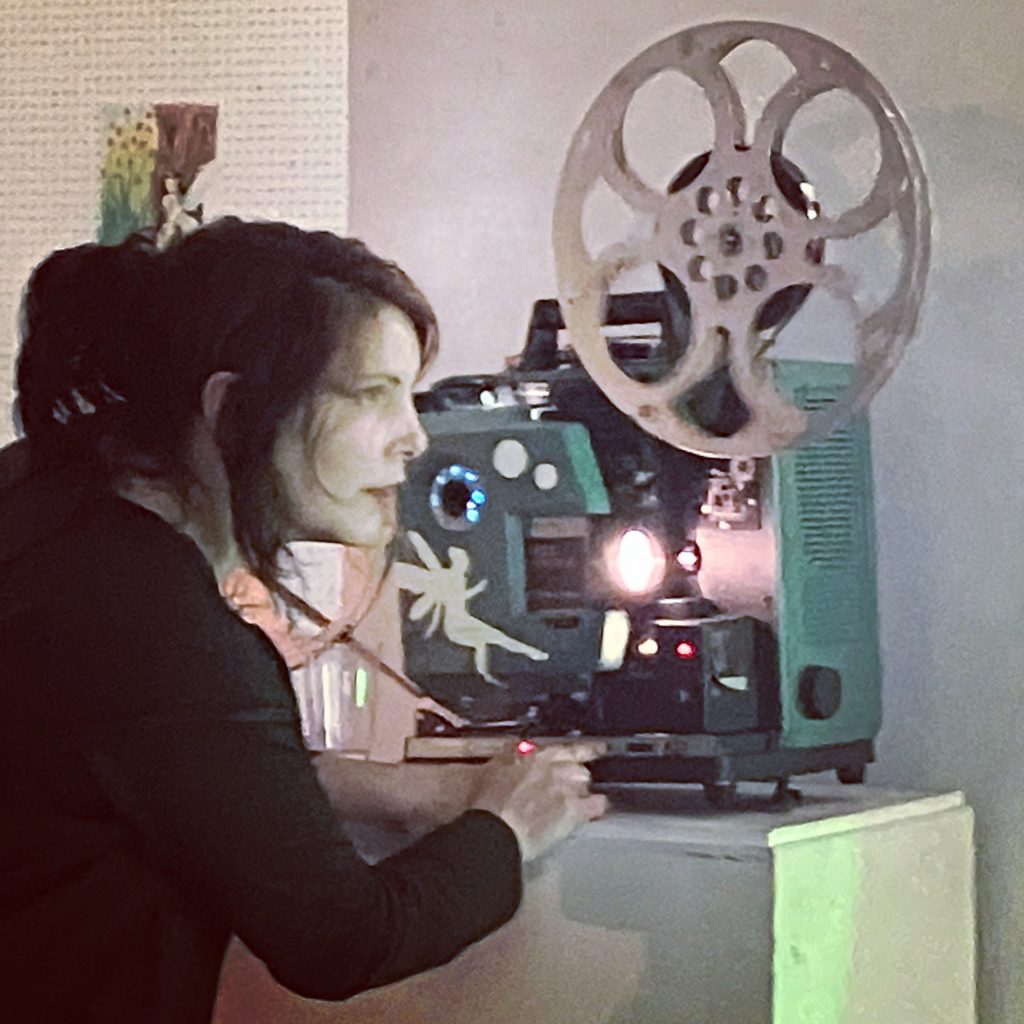

Amy Cutler’s film

Amy created a digitised 16mm 12-minute film which drew on old children’s nature films, 1900s ‘butterfly dance’ films and the original fairy drawings in Princess Mary’s Gift Book (used by Elsie as a model), which played in the installation on a loop. Using tweezers, nail art, glitter, stencils, decorative tape and pink nail varnishes, she restricted herself to tools associated with the bedroom creativity of young girls. In the spirit of Frances and Elsie’s trickery, she aimed to sneak fairies into the machine of cinema — scattering their pixie dust somehow inside the mechanism itself.

With its focus on photographic illusion, supernatural sounds, potentially haunted technology and Arthur Conan Doyle (whose book The Case for Spirit Photography was published in the same year as The Coming of the Fairies), our project had obvious links with the ideas explored by the Media of Mediumship. In particular, the team’s atmospheric installation The Laboratory of Psychical Science, created for the 2021 Being Human festival, had many intriguing overlaps with Tamsin’s fairy soundscape.

So we were delighted to join forces with Christine and Efram to stage Fairy Media, a night of online discussion and performance, during Fairy Light’s 6-week run in Leeds. Holding this event on Zoom added a 21st-century twist to proceedings, with the conversation ranging from the wider history of spirit photography, séances and Spiritualism to the recent Zoom-based horror film Host.

Following last month’s close of Fairy Light, we’re keen to keep developing the project – and we hope it won’t be long before our installation will pop up in another space. Of course, whether the fairies will reappear there too is another matter.

Dr Elizabeth Dearnley is a folklorist and artist whose work explores fairy tales, horror, eerie landscapes and collective storytelling. Currently based at the University of London, she has curated several projects exploring the intersections of folklore and place, including mass diary-writing project The Secret Diary of Bloomsbury, immersive 1940s Red Riding Hood retelling Big Teeth, and the Freud Museum London’s uncanny restaging of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s The Sandman as part of its The Uncanny: A Centenary. She has recently edited an anthology of scary fairy fiction, Fearsome Fairies (British Library, 2021), and is writing a book about the relationship between forests and fairy tales.

More information about Tamsin Dearnley and Amy Cutler‘s work can be found on their respective websites.

[1] Frances Griffiths, Reflections on the Cottingley Fairies – In Her Own Words: With Additional Material by Her Daughter Christine (JMJ Publications, 2009), p. 9.