Dr Efram Sera-Shriar, Science Museum Group

When friends and colleagues speak with me about my research on modern spiritualism, I am often asked if I can show them a cool example of a spiritualist artefact, and to their immense disappointment, I usually hand them a piece of chalk.

While at first this object may seem mundane and insignificant, chalk, and more specifically its role in spirit writing, serves a core function in spiritualist performances. To a certain degree, the foundation of modern spiritualism rests with the professed ability to interact and communicate with the dead, and the ability to receive written messages from spirits remains to this day a popular component of most séances. By starting with a simple object such as a piece of chalk, it is possible to explore a more complex story about the history of modern spiritualism, and in particular, the material culture of its practitioners and believers.

One of the more interesting examples of a medium to use spirit writing in his séances was the American, Henry Slade (1835–1905).

Born near Buffalo, New York, in the hamlet of Johnson Creek, Slade grew up in the heart of the ‘burnt-over district’ in north-eastern United States. Historically, the region was populated by various Christian evangelical groups, and has been described as the place of ‘the second great awakening’ because of the force by which religious revivalism had passed through it. Slade’s hometown was not so far from the family home of the famous Fox sisters, who are often seen as the progenitors of the modern spiritualist movement.

Growing up in this context, Slade was immersed in the rapidly expanding spiritualist movement, and by the age of twelve he began performing as a medium. In the early 1860s, Slade suffered the loss of his wife Allie, who unexpectedly passed away. Soon after, she became the main spirit control in his séances.

Slade’s rise to prominence within the spiritualist community was rapid, and, seeking to broaden his opportunities further, he travelled to England in the summer of 1876 to set up a venue for his séances at 8 Upper Bedford Place in Russell Square, London.

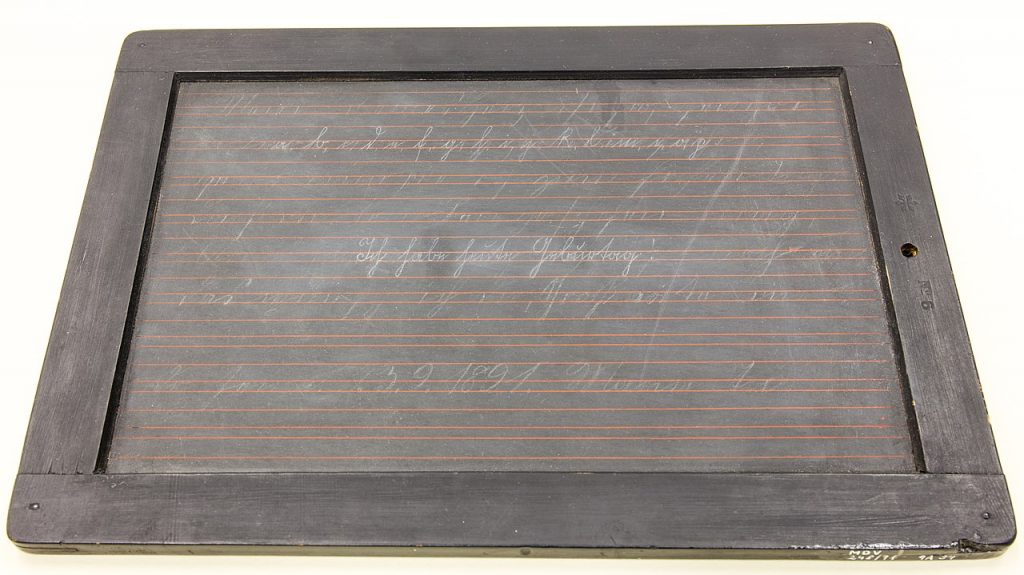

The use of objects was central to Slade’s spiritualist performances, and his main mediumistic feat was the ability to call on spirits to write personal messages to his sitters, using a chalk pencil and a pair of writing slates, without any apparent human physical intervention.

Typically, the chalk was placed between the two blank writing slates and held together with one hand each by both the sitter and Slade. While they waited for a message from the spirits, their free hands would be placed in view on the table. Scribbling noises would inevitably be heard, and when they stopped, Slade would open the writing slates to reveal a newly written spirit message. It was an immensely popular performance and Slade’s clientele grew quickly, with coverage of his amazing feats regularly appearing in spiritualist periodicals such as The Spiritualist Newspaper (f. 1869) and The Medium and Daybreak (f. 1870).

Slade’s good fortunes eventually ended, however, when he was supposedly exposed as a fraud, after the biologist and anatomist E. Ray Lankester (1847–1929) and his friend the physician Horatio Bryan Donkin (1845–1927) attended one of his performances in September 1876. While preparing the writing slates to receive a spirit message, Lankester supposedly seized them from the hands of Slade, only to discover that they contained a pre-recorded message.

Infuriated by the apparent deceit, Lankester set out to destroy Slade’s reputation as a credible medium. He outlined the details of his alleged exposure in a series of letters published in The Times between 16th and 23rd of September 1876.

Eventually, Lankester brought a legal case against Slade under the Vagrancy Act of 1824, which essentially stated that it was illegal in Britain for a person to use any ‘subtle craft, means, or device by palmistry or otherwise,’ to deceive people.[1]

During the court hearing, which occurred throughout the month of October 1876 at the Bow Street Police Court in London, the chalk pencil and writing slates became central to the case. The big question was whether these seemingly normal objects were actually being controlled by spirits, or if Slade was a clever trickster who used misdirection to swap the blank writing slates for ones with pre-recorded messages on them during his performances. As the trial unfolded, other theories came to the fore. One argument was that Slade had a second piece of hidden chalk under his fingernail, which he used to scribble messages on the writing slates, while he held them one-handedly with sitters during the séances.

The prosecution even called on the famous professional conjurer John Neville Maskelyne (1839–1917) to be their star witness and recreate some of the supposed tricks that Slade possibly used to produce the supposed spirit messages. Again, the manipulation of a chalk pencil was central to Maskelyne’s recreation of the supposed spirit phenomenon.

As the key piece of evidence in the case, the chalk came to embody a set of assumption about the veracity of spiritualism. The likelihood that a chalk pencil could be controlled by a spirit tested the limits of accepted naturalistic laws. Without unquestionable proof that spiritual agency was responsible for using the chalk to write the messages at Slade’s séances, the prosecutors could convincingly argue that human agency was the most likely cause, even if the exact mechanism for producing the writing was speculative.

Ultimately, Slade was found guilty under the terms of the Vagrancy Act, but was acquitted through an appeal due to an error in the original indictment paperwork Lankester submitted to the police. Slade fled England before a retrial could take place and never returned.

My purpose in retelling this story about Henry Slade is to emphasise how a seemingly ordinary object like a piece of chalk can have a hidden occultic past. By exploring topics such as spiritualism through their material histories, we can reveal new dimensions to these kinds of historical episodes, one that takes seriously the embodied experience and practices of believers and sceptics alike.

Further Readings:

Edward Clodd, The Question: A Brief History and Examination of Modern Spiritualism, (London: Grant Richards, 1917)

Henry Ridgely Evans, Hours with the Ghosts or, Nineteenth-Century Witchcraft, (Chicago: Laird and Lee, 1897).

Harry Houdini, A Magician Among the Spirits, (London: Harper & Brothers, 1924)

Paul Kutz, A Skeptic’s Handbook of Parapsychology, (Amhurst: Prometheus Books, 1985)

Peter Lamont, Extraordinary Beliefs: A Historical Approach to a Psychological Problem, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Joseph McCabe, Spiritualism: A Popular History from 1847, (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1920).

Shane McCorristine, Spectres of the Self: Thinking about Ghosts and Ghost-Seeing in England, 1750-1920, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Janet Oppenheim, The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850-1914, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985)

Frank Podmore, Modern Spiritualism: A History and a Criticism 2 vols., (London: Methuen & Co., 1902)

John W. Truesdell, The Bottom Facts Concerning the Science of Spiritualism: Derived from Careful Investigation Covering a Period of Twenty-Five Years, (New York: G.W. Carleton and Co., 1883).

[1] Anonymous, “Conviction of Dr. Slade,” The Hull Packet and East Riding Times, 4758 (1876): 3.