Dr Emma Merkling, University of Stirling and The Courtauld Institute of Art

‘Don’t look into his eyes,’ I’m warned. ‘They can hypnotise you.’

I try heeding this advice when I finally find myself in front of the painting in question. Azur the Helper, June 15, 1898 hangs on the far wall of a front room in the Maplewood Hotel. Built originally in 1880 as a horse barn and growing bottom-up over time — to add each new level, the whole building was raised and a new ground floor built — the hotel is among the oldest buildings in Lily Dale, a hamlet an hour outside Buffalo known as the heart of the modern Spiritualist movement. A sign in the lobby requests ‘No Readings, Healings, Circles, or Seances in the hotel’, and on the wrap-around porch mediums mingle with some of Lily Dale’s 22,000-odd annual visitors.

Azur the Helper, June 15, 1898, painting ‘precipitated’ through the mediumship of the Campbell brothers (1898)

This year, Media of Mediumship project lead Professor Christine Ferguson and I are among them. We are visiting Lily Dale — each for the first time — at the invitation of photographer and project collaborator Shannon Taggart to participate in the ‘Science of Things Spiritual’ symposium, a two-day international conference exploring the historical interconnections between spiritualism and science — a theme aligned with the Media of Mediumship’s own. Beyond Christine’s own talk on Anna Kingsford, a Spiritualist and one of the first British women to qualify as a medical doctor, personal highlights include Professor Serena Keshavjee’s explorations of the modernism of ectoplasm photography, and Professor Marjorie Roth’s Tarantella masterclass, which has us hitching up our skirts and playing at spiders in the sweltering Assembly Hall as mediums past gaze down from the walls.

As an art historian in Lily Dale to give a paper on the material culture of science and Spiritualism, I’m determined to take in as much of the community’s material culture as I possibly can. I’ve photographed every Spiritualist lawn sign I encounter; clutched a mug of coffee in the kitchen of medium Dr Lauren Thibodeau; and sat in the heart of the old-growth forest at the Inspiration Stump to observe one of the frequent public demonstrations of mediumship. I’ve walked out to the hamlet’s edge to the site where the Fox Cottage — the birthplace of modern Spiritualism, where the Fox sisters first heard rappings from the spirit world — once stood, relocated to Lily Dale from Arcadia, New York, and lost to a fire in 1955. And now I’m standing in front of Azur because I’ve been sent there by Lily Dale Museum caretaker Ron Nagle, after having poked my head into the museum the day prior to discover a treasure trove.

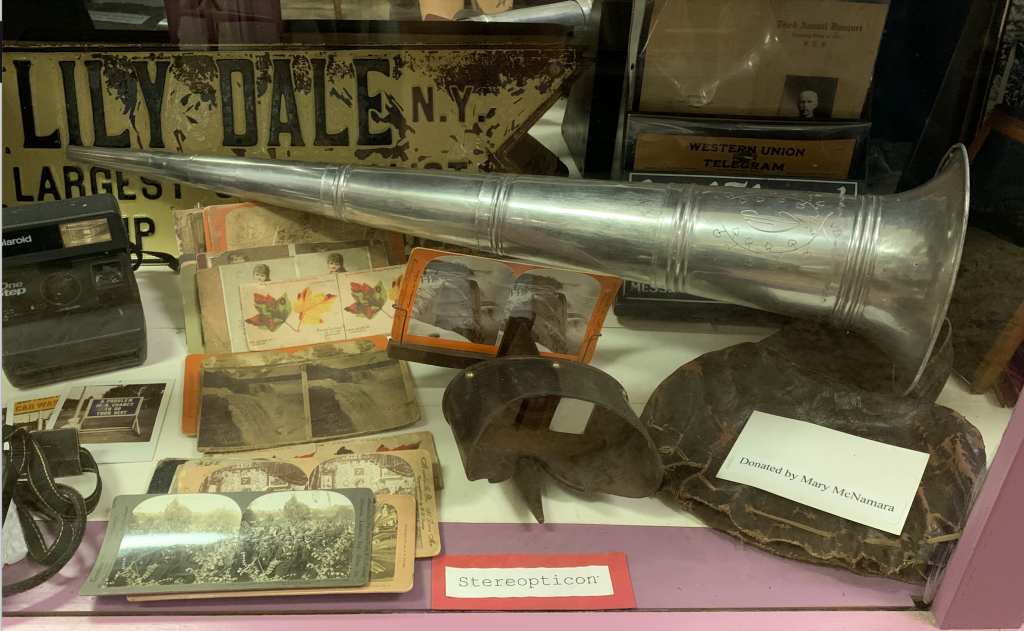

vitrines in the Lily Dale Museum (spirit trumpet, steropticon, and spirit slates)

The Lily Dale Museum’s collection, housed in the hamlet’s old one-room schoolhouse from 1890, is crammed with treasures, from the Fox sisters’ bible (rescued from the fire) to spirit slates bearing messages channelled through famous mediums. The silver spirit trumpets, stacked up on shelves or tucked away in glass vitrines, are among the many objects in the collection I have only ever read about. Given the Media of Mediumship’s focus not only on the material culture of modern occultism broadly, but on technological and scientific objects specifically, it is the historical cameras, Ediphones, wax cylinders, typewriters and other technological artefacts I am most drawn to — objects donated to the museum or collected (he explains) by Ron himself.

a Victrola, Ediphone, and typewriter at the Lily Dale Museum

The talk I have prepared for Lily Dale focuses on similar objects. It centres on the story of the medium ‘Margery’ Crandon, in whose 1925 séances a Victrola gramophone played a starring role. In the Lily Dale Museum, a gorgeous early twentieth-century specimen stands tall in the room’s corner. Ron lets me run a finger along the Victrola’s glossy dark wood, and the plate leaps and spins of its own accord. There is something about seeing this Victrola in the flesh, assessing its size, touching it, that gives me a more direct feel than I’ve had before for Crandon’s séances, and the power of the objects in it.

I get this feeling too as I avoid Azur’s gaze in the Maplewood. The picture’s surface is smooth and uniform; Azur himself glowing white in a featureless black-brown ground from which he seems to lean forward, hand raised in prophecy or benediction. Spiritualists call this a ‘precipitated’ painting, a practice Ron quite literally wrote the book on.[1] Precipitated paintings are said to have been created without the intervention of human hands, developing seemingly miraculously on the canvas in séance conditions, like — in Ron’s words — a polaroid. Azur was produced through the mediumship of the ‘Campbell Brothers’ (the name assumed by duo Allen Campbell and Charles Shourds). On 15 June 1898, six séance attendees joined Allen Campbell one by one in a makeshift séance cabinet in which the blank canvas lay, with no painting materials in sight. As each attendee sat with Campbell, the picture gradually developed. Azur recently travelled to Minneapolis for the exhibition ‘Supernatural America‘, where it hung alongside 1940’s spirit planchettes, Macena Barton’s Untitled (Flying Saucers with Snakes) (1961), and Tom Friedman’s Wall (2017), but to see it here in Lily Dale — in conditions far more closely aligned with its original context — is something else.

views of Lily Dale

These sorts of encounters are both a goal and an unexpected pleasure of our trip. My conference paper is about how rewarding it has been, as Media of Mediumship postdoctoral fellow, to (re)write histories of science and spiritualism through the objects at their heart, but — having undertaken much of my work relatively remotely, during COVID-19 — I have till now had few hands-on encounters with those objects themselves. I know the value of such encounters from my art-historical training, which puts a premium on face-to-face engagement with the work of art, yet it can be easy forget to apply this to more quotidian items. It can also be easy to forget the value of experiencing these objects in contexts beyond the gallery or the archive; not least in spaces where they are curated and cared for by those who believe in their power — a belief we historians often study far too abstractly. The Spiritualist caretaking I witness here better approximates their original function and use than does the white-gloved approach of the academy.

My experience with the objects in the Lily Dale Museum makes tangibly real what my talk preaches in theory: that objects are a key part of the story of science and spiritualism, and that engagement with the perspectives of those who used them — believers in their power as well as the sceptics — is key. Over four days in Lily Dale, I have had the opportunity to speak, for the first time, directly and extensively with practicing Spiritualists — mediums, residents, conference attendees — about their knowledge and present-day experience of some of the historical phenomena I study. Some who attend my talk are learning for the first time about the histories I discuss; others know the cases well, and point me towards relevant archival resources I’ve not yet uncovered. Many are eager to talk about contemporary practices relevant to these historical cases — like how Crandon’s spirit guide is said to still show up in séances from time to time.

I will carry these experiences with me long after.

Dr Emma Merkling is The Media of Mediumship’s Postdoctoral Research Fellow, and Terra Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow at the Centre for American Art (The Courtauld Institute of Art). Her research explores the entangled relationships between history of art, science, and Spiritualism and occultism in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. She co-hosts Drawing Blood, a podcast about art, science, and the macabre.

[1] Scholars Michelle Foot and Massimo Introvigne have also written about ‘precipitated’ paintings. See Michelle Foot, ‘Modern Spiritualism and Scottish Art Between 1860 and 1940’ (PhD thesis, University of Aberdeen, 2016), especially the chapter on David Duguid, pp. 77–113; and Massimo Introvigne, ‘Painting the Masters in Britain: From Schmiechen to Scott’, in The Occult Imagination in Britain, 1875–1947, ed. by Christine Ferguson and Andrew Radford (London: Routledge, 2018), pp. 206–226. For a historical resource, see Edward T. Bennet, The Direct Phenomena of Spiritualism (London: William Rider & Son, [1908]).