Emily Vincent, University of Birmingham

‘…the rooms of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research were thrown open for public inspection’.[1]

— Harry Price, Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter (1936)

Lab coats, test tubes, and an array of musical instruments are not the typical objects one expects to find when confronting the history of ghost hunting. But Aleksander Kolkowski, kitt price, and Laurence Cliffe carefully curated their paraphernalia of the paranormal to animate the ‘Laboratory of Psychical Research’: an auricular reimagining of the historic National Laboratory of Psychical Research (1925 ̶ 1930) founded by renowned paranormal investigator, Harry Price. The intimate Court Room of Senate House played host to the eclectic sound installation and live performances, which ran from the 13th to the 16th of November 2021. This ‘Laboratory of Psychical Research’ was produced with Senate House Library especially for the Being Human Festival, as part of the Media of Mediumship project. The installation uniquely vivified Price’s scientised investigations of the ghostly by recreating the Laboratory and reanimating its historic experiments. Crucially, the installation highlighted how Price’s investigations insisted upon empirical principles and methodologies which capitalised on contemporary media technologies (from the gramophone to the Dictaphone) to examine the claims of those who had experienced visitations from the other side.

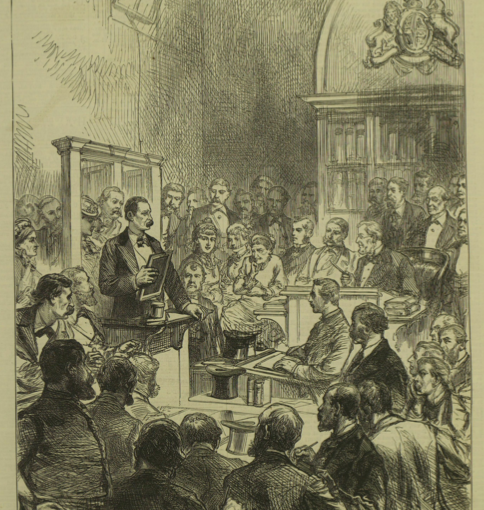

In his captivatingly titled Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter (1936), Price claimed that his Laboratory emerged following the post-war ‘wave of interest in the possibility of an after-life [which] swept the country like a tornado’. Navigating away from what he deemed the ‘purely emotional’ bereaved and an overly-hopeful spiritualist community, he instead gravitated towards those he considered the ‘few sane people’, who ‘demanded that the alleged phenomena said to be produced in the séance-room should be scientifically investigated by qualified and unbiased persons’.[2] Crowning himself Director, Price founded the Laboratory in South Kensington to create a space in which the scientific and the supernatural converged. As exemplified in the above image, the Laboratory was ‘properly equipped for scientific observation’ and juxtaposed the study of ostensibly intangible spectral apparitions and apparently invisible psychical activities — such as telekinesis — with a distinctly scientific space which enabled him to record, measure, and analyse the paranormal.[3] Media technologies were at the heart of Price’s experimental endeavours: thermographs measured fluctuating air temperatures, Dictaphones recorded séance activities, gramophones captured the sounds of entranced breathing, and cameras were invaluable equipment in Price’s ‘ghost-hunter’s kit’.[4] Upon entering Senate House, it seemed especially fitting that Price’s historic ‘Library of Magical Literature’, a collection of over 13,000 books, photographs, and ephemera concerning magic, the supernatural, and related pseudo-scientific phenomena, was also housed just a few floors above.[5]

Within the ‘Laboratory of Psychical Research’, Price’s investigations were visually and aurally brought to life (or, to life after death) via an app on each visitor’s smartphone. The intuitive smartphone app was specially developed by Laurence Cliffe at the University of Nottingham’s Mixed Reality Laboratory — a modern-day interdisciplinary lab developing research on Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) — and worked by scanning QR codes found on ‘Telepatha’ cards located on the objects around the room.[6] Focusing a camera on the ‘Telepatha’ cards triggered recordings which modulated eerily according to the user’s proximity to each object; this created an uncanny listening experience particularly appropriate for the installation’s spectral themes. Each sound was complemented by informative on-screen descriptions which usefully contextualised the material of Price’s Laboratory. Here, it is worth reflecting on the self-referential nature of the installation itself. It seemed especially apt that the user-driven smartphone tour echoed Price’s device-driven spectre-seeking. It also reinforced the suitability of the smartphone (integrated with the kind of powerful cameras and ultra-sensitive microphones that Price could only have dreamed of) in fulfilling the same ghost-hunting role during the installation. Similarly, the app’s functionality amplified many of the uncanny sensations that Price was so compelled by: unexpected voices from the dead, discordant music, and incongruous visual and aural phenomena.

Visitors were first greeted by this arresting photo of Price, whose interrogative stare was hard to escape. An opening interview with Price from 1936 stressed his belief that psychical research had been too confused with spiritualism; he insisted it was now a ‘science’, one which was ‘rapidly becoming an exact science’.[7] Price’s interview delineated two types of psychic activity: the mental (concerning clairvoyance and direct voice manifestations), and the physical (those apparitions connected to poltergeists and haunted houses).

Next was a gramophone playing the overture to ‘Oberon’ by Carl Maria von Weber, which was interspersed with discordant harmonica and rapping sounds, replicating an unnerving Laboratory séance recording from 1926. Alongside this was a thermograph, modelled on the exact one Price used to measure temperature fluctuations.

Visitors were then invited to enter the evocative curtained séance enclosure, populated by a table, tambourine, and gloved ‘ectoplasmic’ hands, which played a striking recording of a public séance held by spiritualist Noah Zerdin on 28th April 1934 at London’s Aeolian Hall. With his authoritative voice, the medium announced that he held the ‘keys’ to ‘unlocking the doors to the other life’.[8]

The fourth object in the installation was a bellows camera which prompted the disturbing trance breathing sounds of Austrian psychic subject Rudi Schneider. Writing in his memoir, Price recalled the remarkable quality of Schneider’s breathing, observing that: ‘this rapid respiration sometimes reaches two hundred and sixty cycles per minute — or even more. This trance breathing was hailed by the uninitiated as so remarkable — or even supernormal — that a gramophone record was made of it and, very unfortunately, broadcast on two occasions’.[9] As revealed by the ‘Telepatha’ card, Price later used the bellows camera to ‘expose Schneider’s fraudulent activities during a séance on 28th April 1932’.[10] The evident utility of the camera and gramophone as documentary tools for psychical research reinforced Price’s use of diverse technologies in testing the integrity of his experimental subjects.

Pictured above, the Dictaphone was an important administrative media tool for the Laboratory’s séances. Installation visitors listened to the methodological observations of Price’s research assistant Miss Lucy Kay, who dictated to the machine away from the séance circle. Kay’s brisk voice relayed notes from the sitting of medium Stella Cranshaw (known as ‘Stella C’), whose experiences of telekinetic manifestations were the focus of the Laboratory’s inaugural experiments. Time stamps revealed the encroaching presence of purported ghostly activity, the increasing pace of which was especially exciting to hear: ‘5.37: cold breezes, bells rang […]. 5.42: Mr Price feels a cold breeze on his hand […]. 5.52: two sets of raps heard’. Encountering this recording enabled listeners to embody Kay’s observant role. Like Kay, visitors became external witnesses to the alleged supernatural phenomena as it unfolded. By allowing us to step just outside of Stella C’s séance circle, visitors could reflect upon the necessary voyeurism, and dedicated recording required, for Price’s investigations to succeed.

The installation’s adjacent chemistry paraphernalia (including the aforementioned test tubes) replicated the approaches that Price employed to animate ‘The Detector’: a device developed after he had accidentally wired himself into a radio receiver. An interview with Price from 1936 conveyed to visitors his staunch enthusiasm that psychical research was progressing, specifically in appealing to ‘orthodox science’. To substantiate this, he evidenced engagement with the international academic community, citing interest from Leiden and Duke Universities, as well as the University of London, as proof of the Laboratory’s global legitimacy.[11] Price emphasised his personal investment in the chemistry of psychical research, stating that ‘the various chemicals, etc., were taken from my private laboratory and are what I used in photography, microscopy, etc.’. He then outlined how these various fluids enabled the mechanical function of ‘The Detector’: ‘these substances were placed in the detector (usually in a liquid form), so that whatever the position of the detector, the contents of the container were connecting the two brass electrodes’.[12]

Finally, the installation closed with a vibrant and eclectic live performance by sound artists Aleksander Kolkowski and kitt price, who resurrected Stella C’s transcripts and boldly performed readings of Price’s experiments, as detailed in Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter. The once-daily performance also involved a slideshow with rare photographs from the archives which depicted the cast of a spirit hand, Price taking detailed notes, and others capturing the quotidian routine of the Laboratory’s experiments. Clad in lab coats, Kolkowski and price were entertaining, thought-provoking, and humorous, and audiences responded well to the vivid recreation of what the science of the supernatural looked like. Their performance was further enhanced by the intimate atmosphere that the limited audience encouraged, one which invited a greater focus on the testimonies of the Laboratory’s subjects. Ultimately, it was as if visitors had stepped back in time to peer through the panes of Price’s Laboratory windows.

All in all, the ‘Laboratory of Psychical Research’ was an immersive and well-researched installation which both visually and aurally reanimated Price’s paranormal experiments, while focusing on his investment in contemporary media technologies. By amplifying the aurality of Price’s technologies, the installation gave much-needed attention to the soundscapes so crucial to a deeper and more well-rounded understanding of early-twentieth-century psychical histories.

Emily Vincent is a final-year PhD researcher in English Literature at the University of Birmingham. Emily’s thesis examines how women writers confronted child loss in their fin-de-siècle supernatural fiction. She examines the importance of Spiritualism, maternity, and domestic architecture in the supernatural works of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Florence Marryat, and Margaret Oliphant. At Birmingham, Emily is a Teaching Associate for the ‘Decadents and Moderns’ module and co-founded Gothica, an interdisciplinary reading group exploring the role of the Gothic in literature and culture. For more information, visit Emily’s doctoral research profile, or get in touch via email ESV939@student.bham.ac.uk, or on Twitter @Emily__Vincent.

[1] Harry Price, Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter (1936), p. 38

[2] Price, Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter, p. 15.

[3] Price, Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter, p. 109.

[4] Price, Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter, p. 39.

[5] https://london.ac.uk/senate-house-library/our-collections/special-collections/printed-special-collections/hpl

[6] https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/mixedrealitylab/

[7] ‘Interview with Harry Price’, Movietone News, 31 December, 1936.

[8] Telepatha card description. With thanks to Dan Zerdin and the British Library.

[9] Price, Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter, p. 235.

[10] Telepatha card description. With thanks to the Society for Psychical Research.

[11] Telepatha card description. Recording from ‘Interview with Harry Price’, Movietone News, 31 December 1936.

[12] Price, Confessions of a Ghost-Hunter, p. 260.