Luis Fernando Bernardi Junqueira (林友樂), University College of London & Wellcome Trust

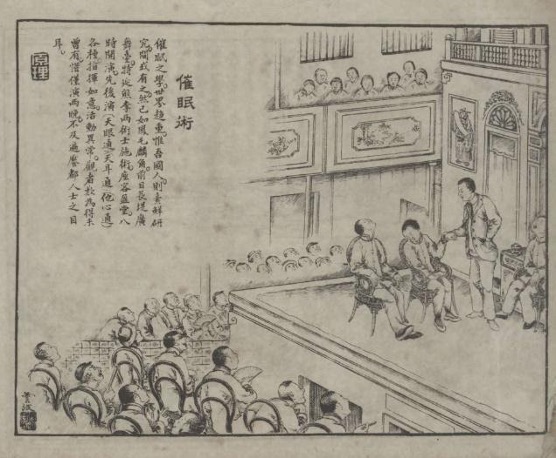

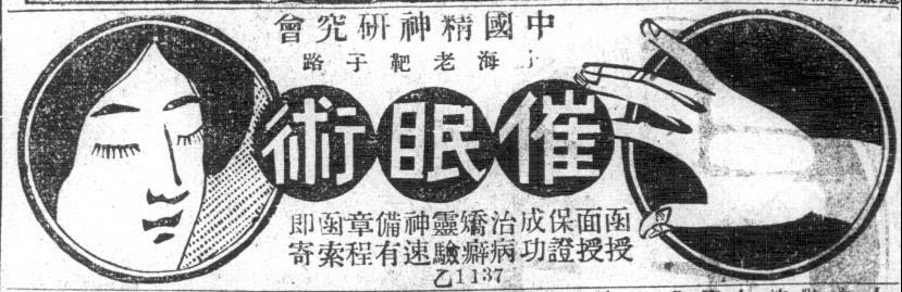

Figure 1: Advertisement for in-person and distance courses of hypnosis offered by the Chinese Association of Hypnotism. Shenbao 申報, 27 February 1922

Known in Chinese as ‘Spiritual Science’ (xinling kexue 心靈科學), psychical research was introduced into China from Japan in the 1900s and soon took the country by storm. Inspired by such prominent associations as the Society for Psychical Research (London), the American Society for Psychical Research (New York) and the Institut Métapsychique International (Paris), similar groups devoted to the scientific study of the mind and paranormal phenomena mushroomed in Republican China (1912–1949). At its heyday in the 1920s, Spiritual Science materialised into well over twenty transnational networks, bringing together Chinese students from such varied places as North and Latin America, Western Europe, Africa and Southeast Asia.

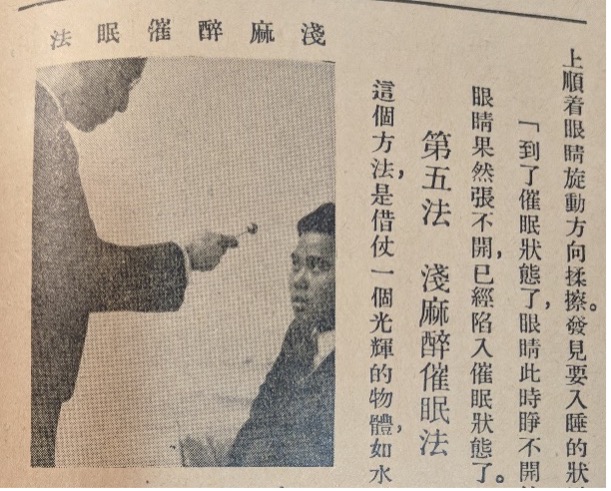

Following the ‘hypnosis boom’ in fin-de-siècle Japan, hypnosis sparked a furore in early twentieth-century China. A hallmark of Spiritual Science, hypnosis was vigorously promoted in the Chinese press as a new science that transcended the segmentation and reductionism of the physical sciences by looking at reality in both its material and spiritual dimensions. Newspapers, magazines and tabloids advertised it as the most innovative branch of Western medicine, a powerful mind-cure technique celebrated amongst Western and Japanese educated elites – a science the Chinese should master in order to enter ‘the new era’ (xin jiyuan 新紀元).

Hailed as an instrument of change, hypnosis represented the hope to save China from the political, moral and social degeneration it had gone through since the mid-nineteenth century. Based on the principle that every human being has the potential to realise his or her own ‘spirit’ (xinling 心靈), Spiritual Scientists advocated the use of hypnosis as a means for crafting the ‘modern Chinese citizen’ (renmin 人民) and thereby thoroughly accomplishing the Chinese revolution. It became the medicine that would heal China.

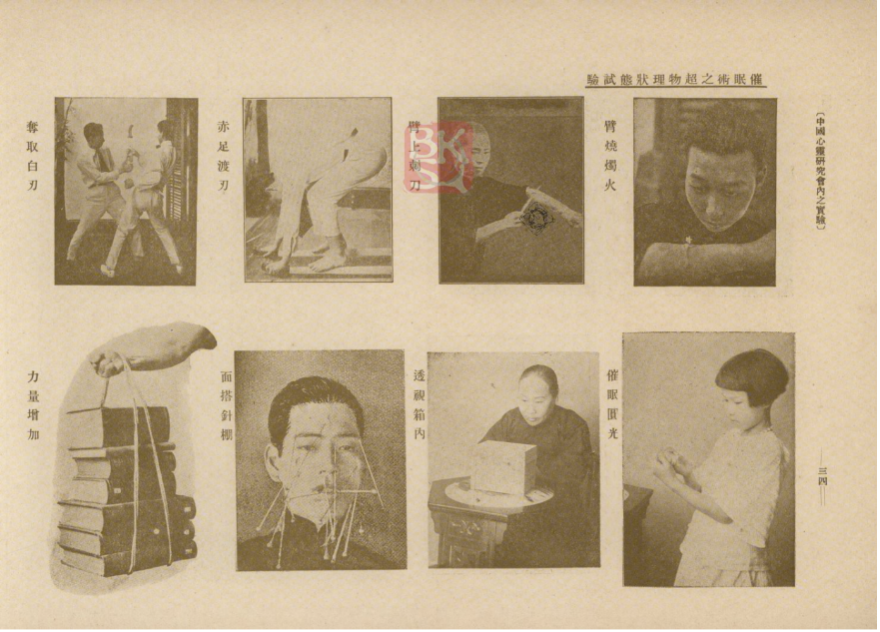

All this, Spiritual Scientists repeated, because hypnosis was an experimental and experiential science of the mind. Often dressed in Western attire – the epitome of progress – Chinese stage hypnotists promised to reveal, in an empirical and impartial manner, the marvellous effects hypnosis could produce, from self-healing to the development of such psychic abilities as telepathy, clairvoyance and spirit-communication. In short, hypnosis opened up unprecedented possibilities for anyone, both men and women, to directly access the innermost mysteries of life.

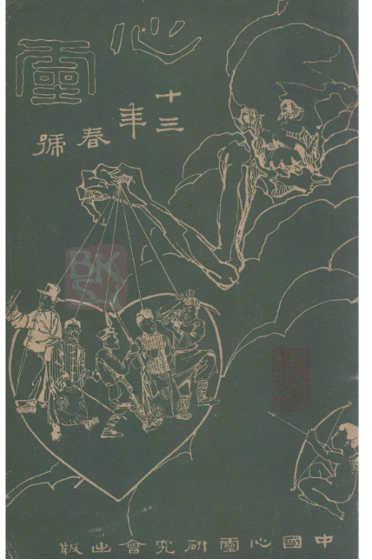

The Chinese Institute of Mentalism (Zhongguo xinling yanjiuhui 中國心靈研究會), one of the earliest, largest and most influential associations of Spiritual Science in Republican China, played an enormous role in the dissemination of hypnosis throughout Chinese society. With branches all over the world, the Institute offered a wide array of in-person and distance courses to anyone interested in unlocking the full potential of their mind. Not only did the Institute edit monthly and annual periodicals for almost twenty years, but it also published over fifty manuals covering such subjects as hypnotherapy, telepathy and mind-cure, many of which were translations from English, French and especially Japanese.

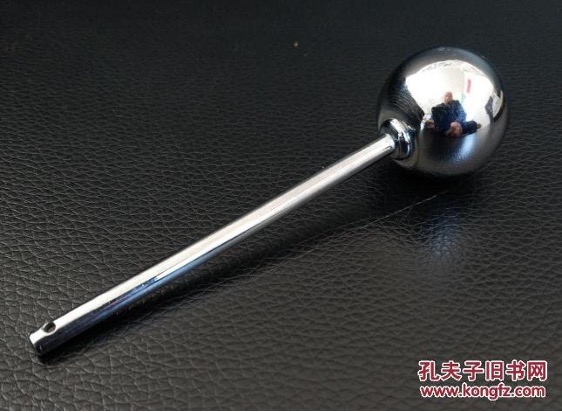

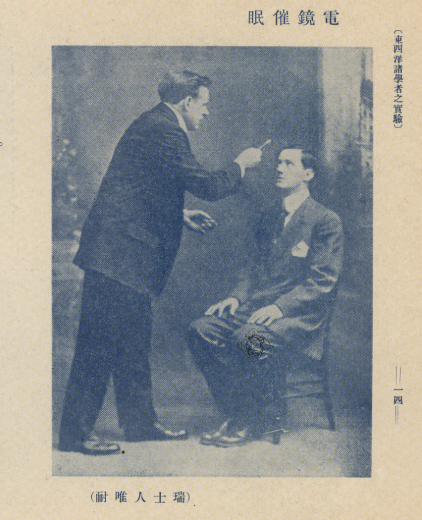

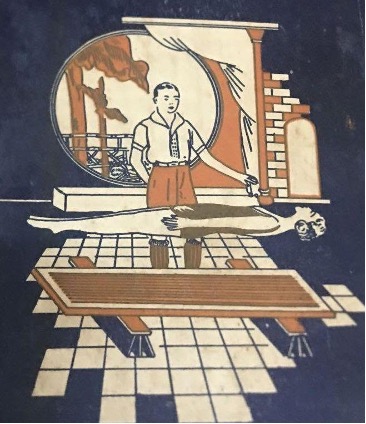

The ‘method of electric hypnotism’ (dianjing cuimianfa 電鏡催眠法) stood amongst the Institute’s most acclaimed innovations (Figures 8–9).

Electric hypnotism consisted of both a method and a tool. Despite its name, the metal device did not emit any external electric current but rather promised to excite a kind of inner electricity lying dormant in our bodies (rendian 人電), an energy that helped the individual enter the hypnotic state with ease. Invented by the Institute’s life-longest director, Yu Pingke 余萍客, in the 1920s, electric hypnotism was admittedly inspired by the Knowles Radio Hypnotic-Crystal (Figures 10–12), a device created by the world-renowned occultist Elmer E. Knowles (1861–1959) for hypnotherapy and attention focus. It also owned a great deal to Furuya Tesseki 古谷鉄石, a celebrated Japanese hypnotist who invented the ‘double hypnotic ball’ (fukushiki saimin-kyū 複式催眠球, Figure 13) and eventually became Yu Pingke’s main teacher.

Just like in the North and Latin America, Europe and Japan, hypnosis in China went far beyond today’s understanding of it as a mere technique for attention focus. The self-experience of entering the hypnotic state led a number of Chinese intellectuals and social reformers to notice certain similarities between Western hypnosis and traditional Chinese occult arts such as talismanic healing (zhuyou 祝由), spirit-writing (fuji 扶乩) and meditation (jingzuo 靜坐). In order words, hypnosis seemed to provide a scientific framework through which to clarify the efficacy of Chinese occult arts.

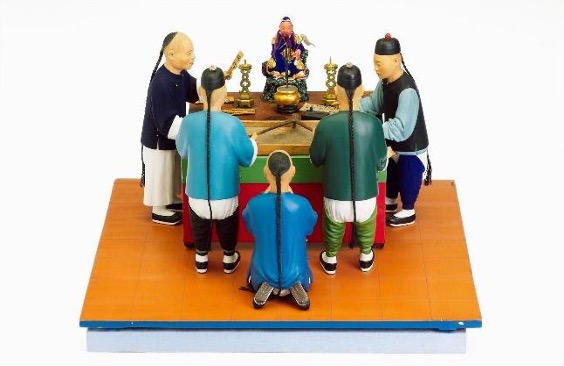

The case of spirit-writing, or fuji, is particularly interesting in this regard. In China, fuji consists of a ritual in which mediums communicate with the spirit world through writing using a T-shaped device, the ji 乩. The earliest records of spirit-writing date from the Song dynasty (960–1279), and it remained strikingly popular amongst the Chinese gentry up to the 1940s. Indeed, while it has almost disappeared in Mainland China, spirit-writing is still very much part of the everyday life of Chinese communities in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and Southeast Asia.

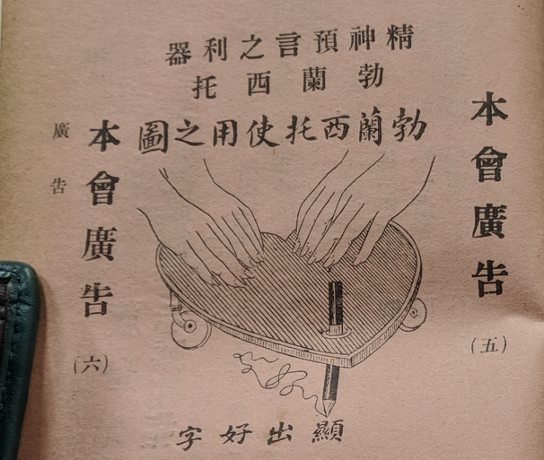

As early as the 1870s, Western Christian missionaries in China were already pointing out the remarkable resemblance between Spiritualism, particularly automatic-writing, and the Chinese fuji. But with the popularisation of Spiritual Science in the first half of the twentieth century, fuji gained a new lease of life. Drawing on works of psychical research and hypnosis in English, French and Japanese, Spiritual Scientists sought to explain spirit-writing in terms of the Unconscious (qianzai yishi 潛在意識) or multiple personalities (renge bianhuan 人格變換), concepts just introduced into the Chinese vocabulary. Contrary to what old-fashioned materialists naively claimed, Spiritual Scientists declared, spirit-writing was not superstition. It truly worked. But its efficacy should not be attributed to disembodied souls as the folks of yore had done; rather, everything was the work of the all-powerful mind or ‘spirit’ (心靈). As such, with the support of the Chinese ji or the Western planchette, hypnotised subjects could obtain information about events happening far away in time or space – and sometimes even receive messages from the dead.

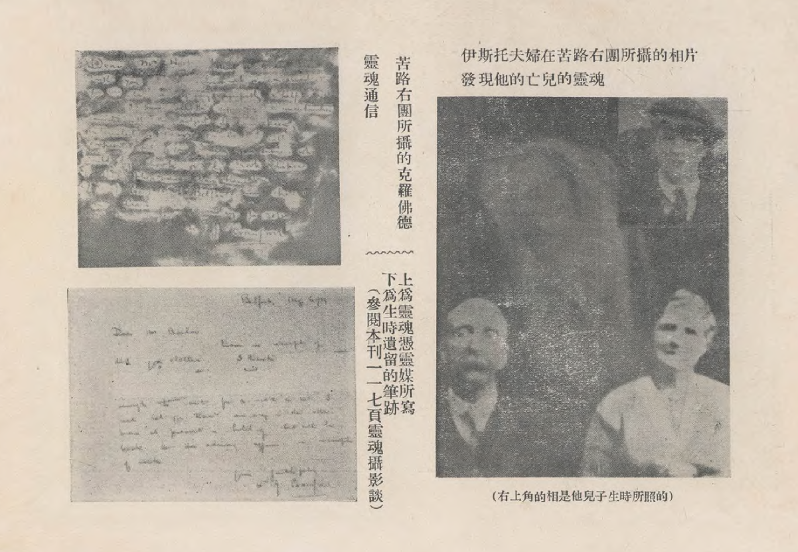

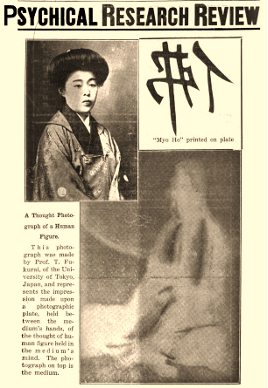

Spirit photography also became a major concern amongst Spiritual Scientists, both in Japan and China. In the early 1900s, Fukurai Tomokichi 福来友吉 (1869–1952), a hypnotist and professor of psychology at the prestigious Tokyo Imperial University, discovered ‘thoughtography’ (nensha 念写), the ability of certain individuals to project mental images onto the photographic film.

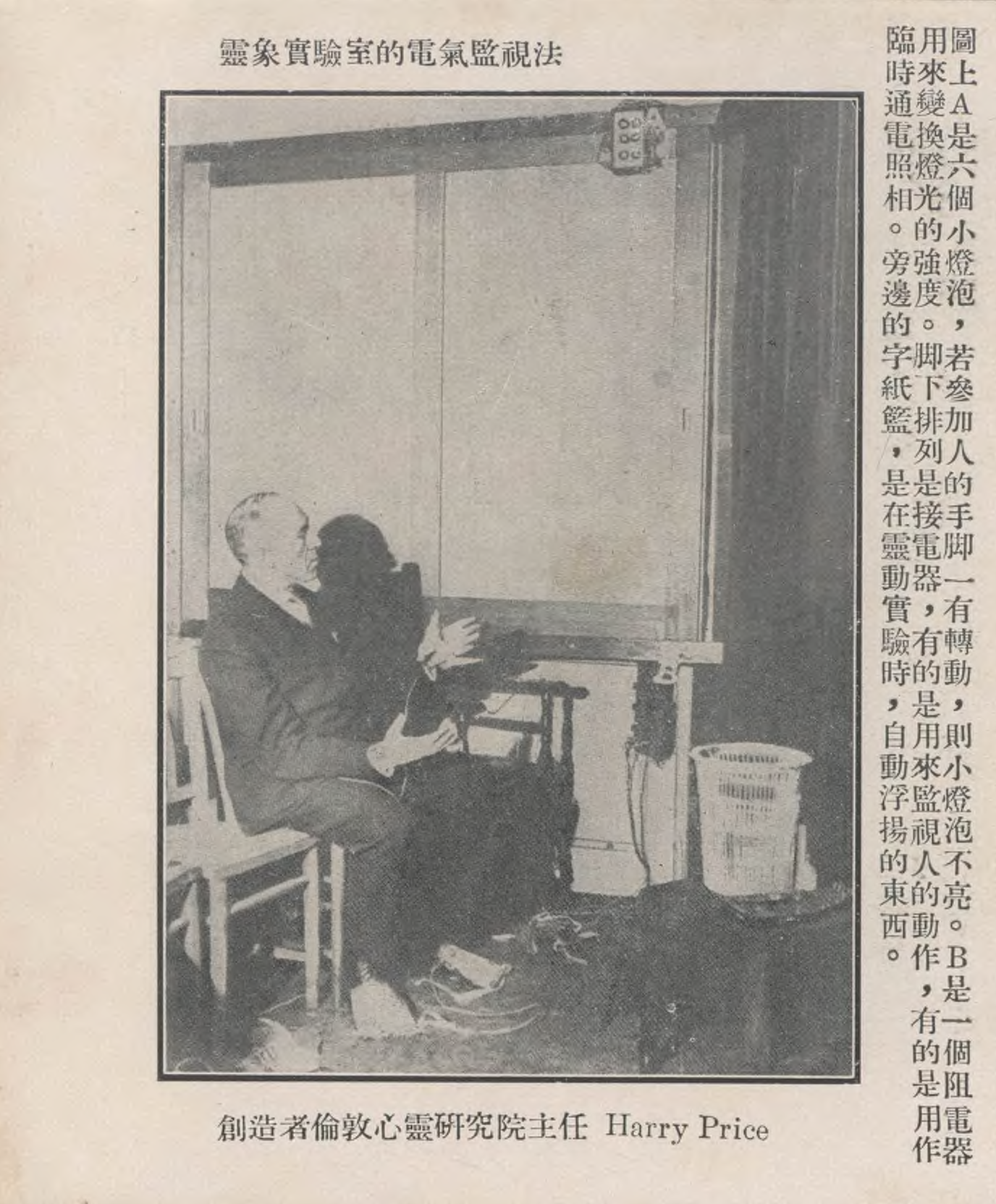

Fukurai’s discovery took place while he was studying hypnotised subjects in the 1910s, especially the female clairvoyants Mifune Chizuko 御船千鶴子 (1886–1911) and Nagao Ikuko 長尾郁子 (1871–1911). Largely criticised in Japan, Fukurai became a hero in Republican China. From the 1910s to the 1930s, Chinese Spiritual Scientists engaged eagerly in spirit photography and thoughtography, activities whose scientific legitimacy was backed by the figures of eminent Japanese and Western psychical researchers, including Fukurai, Arthur C. Doyle, William C. Crookes, Charles Richet and Harry Price.

Spiritual Science emerged as the Chinese response to global anxieties stirred up by scientific materialism and religious doubt, and its history transcends the limitations of national borders or local concerns. The movement challenged the dichotomies of ‘Chinese versus Western’ or ‘science versus religion’ which Chinese historiography has long taken for granted. Spiritual Science is a history of entanglements, wherein the occult was redefined as an essential part of modernity, as the substratum of a new way of making science.

Luis Fernando Bernardi Junqueira (林友樂) is a PhD student in the Department of History at UCL, funded by the Wellcome Trust. His doctoral project looks at the transnational history of psychology and psychical research in early twentieth-century China, their impact on healthcare and religious experience. For more information, including a list of publications, please visit https://luisfbj.com/. Email: youle.junqueira@gmail.com or l.junqueira@ucl.ac.uk.