Dr Brian McCuskey, Utah State University

In July 1883, the landscape photographer William Harding Warner announced ‘a new scientific subject’ in the British Journal of Photography. Warner had been experimenting with stereoscopic photography since the 1850s, but he was now working in a different dimension, trying to capture images of ‘Od’, a colorful radiant energy, on his gelatin-bromide plates. Od was the universal life force that the German chemist Carl von Reichenbach had first hypothesized in the 1840s but never been able to prove empirically. However, Warner declared he had finally ‘succeeded in photographing a plant in its natural colours’, sending the Journal a detailed explanation of Od as well as a photograph of some geraniums, ferns, and a rubber plant. Though the print was black-and-white, he claimed traces of Odic color could still be detected, even if ‘more clearly seen by some persons than others’.[1]

One week later, a young Portsmouth physician named Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a letter to the editors, expressing skepticism. ‘Mr. Warner cites as facts things which are incorrect, and that in a crisp and epigrammatic way which is delightful,’ Doyle scoffed. ‘From these so-called facts he draws inferences which, even if they were facts indeed, would be illogical, and upon these illogical inferences draws deductions which, once more, no amount of concession would render tenable.’[2]

Doyle’s characterization of Warner perfectly describes the manner and method of another amateur Victorian scientist: his own Sherlock Holmes, who delights readers precisely because he sees clearly what others cannot. Detecting the scarlet traces of crime that persist invisibly at the scene, he constructs chains of logical reasoning that often defy both logic and reason.

What happened between 1883, when Doyle indicted Warner for his pseudoscience, and 1887, when Doyle introduced Holmes in A Study in Scarlet, which presents the same untenable method as ‘the Science of Deduction and Analysis’?

Doyle answered this question himself on camera, in a Movietone newsreel interview shortly before his death in 1930, by which time he was the world’s most famous and well-traveled spiritualist.

In the newsreel (above), he discusses his absolute conviction—not personal belief but factual knowledge—that the dead communicate with the living. ‘Curiously enough,’ he observes, ‘my first experiences in that direction were just about the time when Sherlock Holmes was being built up in my mind.’ The record shows that his conversion dates even more precisely to July 1887, when he wrote to the spiritualist magazine Light about his recent experience at a séance, declaring ‘the truth of this central all-important fact.’

Four months later, Scarlet was published, and Holmes began his long and highly successful career as an apologist for pseudoscience, helping his author convert so-called facts and illogical inferences into belief that seems like knowledge. By the 1920s, Doyle had disavowed Holmes, worried that popular fiction compromised more serious work. However, his writings on spiritualism during that decade use the same crisp and epigrammatic language and make the same illogical leaps as both Holmes and Warner before him. Most famously, as Professor Christine Ferguson discusses, that method led Doyle to accept the ‘Cottingley Fairies’ photographs at face value.

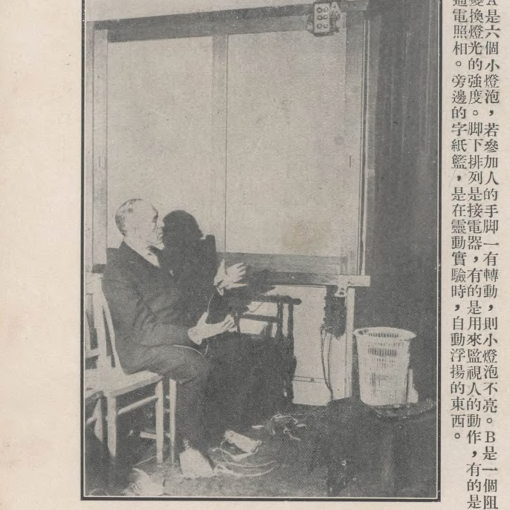

When pushed, Doyle fell back on his character, appealing to fictional scientific authority. In 1925, he opened his Psychic Bookshop and Museum in London, exhibiting the media of mediumship, especially the variety of spirit photographs and slate writings that Dr Efram Sera-Shriar describes. The London Daily News expressed skepticism, wondering how the creator of Sherlock Holmes could be as credulous as Dr Watson.

Doyle replied to set the record straight once and for all: ‘[The Daily News] couples my name with Sherlock Holmes, and I presume that since I am the only begetter of that overrated character I must have some strand of my nature which corresponds with him. Let me assume this. In that case I would say (and you may file the saying for reference) that of all the feats of clear thinking which Holmes ever performed by far the greatest was when he saw that a despised and ridiculed subject was in very truth a great new revelation and an epoch-making event in the world’s history.‘[3]

Of course, Sherlock Holmes himself pulled up far short of that otherworldly conclusion. ‘The world is big enough for us,’ he says in ‘The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire,’ adding, ‘No ghosts need apply.’ But that never stopped his author—nor has it stopped many of his fans ever since—from applying his methods.

Brian McCuskey is an associate professor of English at Utah State University, and the author of How Sherlock Pulled the Trick: Spiritualism and the Pseudoscientific Method (Penn State University Press, 2021).

[1] William Harding Warner, ‘A New Scientific Subject’, British Journal of Photography, 13 July 1883, 406.

[2] Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The “New” Scientific Subject’, British Journal of Photography, 20 July 1883, 418.

[3] Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The Psychic ‘Gloves’, Daily News (London), 9 December 1925, 3.