Dr Efram Sera-Shriar, Science Museum Group

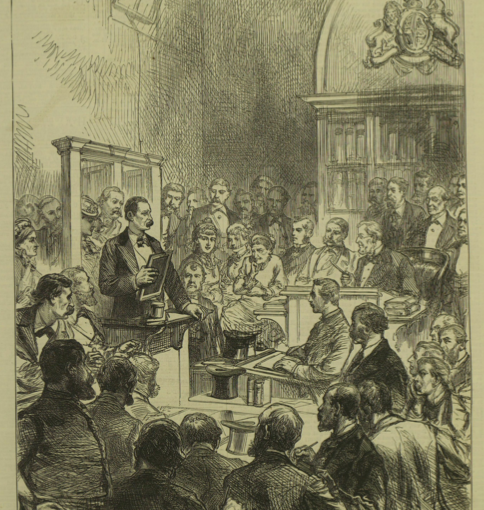

In 1882 the artist and spiritualist Georgiana Houghton published a photobook called Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye. Its aim was simple: to provide a compelling set of photographic evidence that affirmed the veracity of the spirit hypothesis, namely, the idea that the phenomena produced by mediums at séances are caused by disembodied spirits.

As Houghton explained in the ‘Preface’ to her book, she was anxious about sharing these materials with a broad readership until she had collected sufficient examples that in ‘reproduced form’ they could ‘carry a weight of evidence as to the substantiality of spirit beings.’ If she could provide a persuasive set of materials for readers to review, she believed that the evidentiary robustness of spirit photography would transcend ‘any other form of mediumship.’ [1]

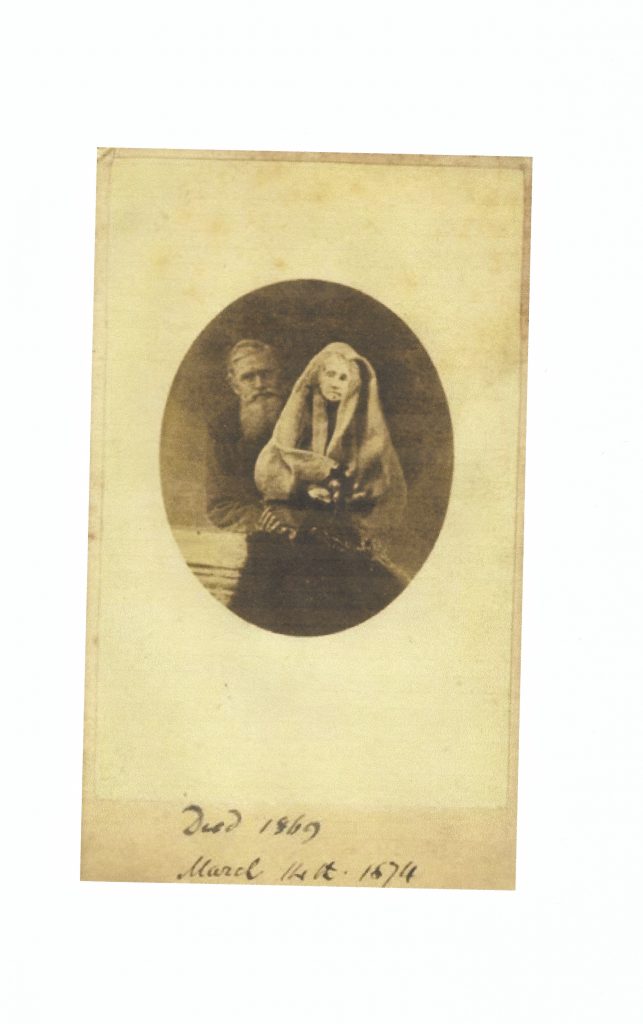

In total, the book contained 54 miniature reproductions of images, taken by the renowned Victorian spirit photographer Frederick Augustus Hudson, who is widely regarded as the originator of spirit photography in Britain. Houghton’s book encloses an impressive collection of images, with numerous high-profile figures from the nineteenth-century British spiritualist community, including a photograph of the naturalist and co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace, and the supposed spirit of his mother, Mary Anne Wallace (née Greenell).

Houghton also appeared in several of the images from the book, including the one below, where she is pictured sitting in a chair with the Victorian mediums Mary Elizabeth Tebb and Agnes Guppy-Volckman standing on either side of her. Hovering around them is an alleged unknown spirit entity. The inclusion of these personal images was significant, because it demonstrated that Houghton was directly engaging spirit photography and could combine her first-hand experience working with spirit photographers with a sound knowledge of examples appearing in the extant spiritualist literature.

A significant issue for Houghton, as for many spiritualists, was that reproduced versions of spirit photographs were often deemed less convincing as sources of evidence in support of the existence of spiritual entities. There were many factors as to why this was the case, but, fundamentally, it was argued that much of a spirit photograph’s authenticity was lost during the reproduction process. Despite these concerns, Houghton believed that her book, Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings, managed to replicate credible copies of the original images.

What is revealing about Houghton’s discussion on the credibility of the photographic reproductions in her book is how important the materiality of the original images was for establishing the veracity of spiritualism. Prints appearing in books could be easily faked, but if the reliability of the production process could be shown, they would be seen as undoubted proof of spiritual existence.

Houghton, therefore, took great care to describe the process of creating these images, to assure her readers that no forgery was involved. The photographs, she explained, were ‘executed by the Albertype process, which has the same advantage as photography in taking a true copy by a species of negative, from which the plates are afterwards printed by a permanent method, and will therefore not fade away as the photographs are too apt to do.’ [2] Thus, the images produced for Houghton’s book were professedly made to the highest standard, with a view to endurance in mind, so that the originals could be used for future investigations.

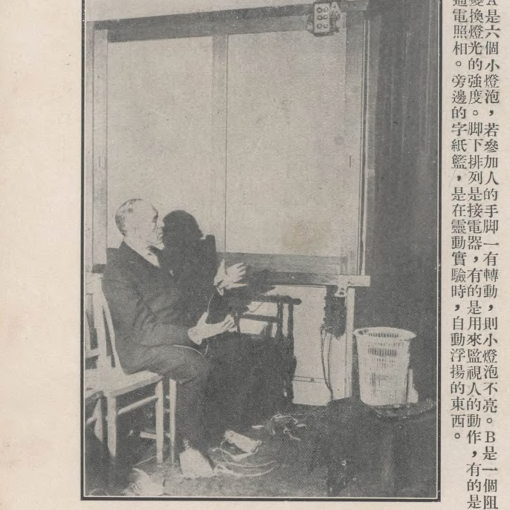

The well-known photographer William Elliott Debenham owned a studio on Regent Street in London, and Houghton entrusted him with the duty of overseeing the production of the spirit photographs for her book. Debenham outlined in a letter to Houghton, which is reproduced in the ‘Preface’ to Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings, how he was ‘nearly always present’ when the photographic plates were prepared by Hudson, and he ‘marked them with a diamond’ to ensure that they could not be switched with others without detection. On some occasions, Debenham even went so far as to prepare the plates himself in advance of the photographic sessions. Debenham also maintained that he was always present in the darkroom when the photographs were developed by Hudson. These controls were used to limit the opportunity for forgery to occur.[3]

According to Debenham, the quality of the kinds of spirit photographs produced during a session depended much on the health of the photographer: if they were ill, their ability to capture genuine spirit phenomena lessened. During the course of producing photographs for Houghton’s book, Debenham claimed that Hudson fell ill and many of his attempts to capture spiritual entities in images failed. Thus, to boost their chances of producing better results, Debenham invited the well-known Victorian medium Lottie Fowler to attend the sessions and encourage spirit activity. This, Debenham claimed, was successful.

Houghton’s Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings is an interesting read, and reminds us of how important the material culture of media technology was for spiritualists. Even though many of the figures involved in the production of the book would later be discredited as charlatans — including Hudson, who in 1872 was exposed as a fraud by the editor of The Spiritualist Newspaper, William Henry Harrison — the book remains a wonderful source for understanding how Victorian spiritualists supported their beliefs, and what counted as trustworthy evidence in spirit investigations.

In 2016, The Courtauld Gallery in London held an exhibition of Houghton’s art entitled ‘Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings’. Houghton produced astounding watercolours like The Eye of God (c. 1862, see below) in a trance state, as she channelled spirit energies which caused her hand to move involuntarily on the paper. In workshop organised alongside this exhibition, PI of ‘The Media of Mediumship’, Professor Christine Ferguson, presented on the relationship between Houghton’s art and photography.

[1] Georgiana Houghton, Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings (London: E. W. Allen, 1882), v.

[2] Georgiana Houghton, Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings (London: E. W. Allen, 1882), v.

[3] Georgiana Houghton, Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings (London: E. W. Allen, 1882), vi.

All images are from Georgiana Houghton, Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings (London: E. W. Allen, 1882), unless stated otherwise.