Scarlett McQuillan, University of Stirling

Hafed in Glasgow: Oriental Occulture in late-Victorian Scotland

By Scarlett McQuillan, University of Stirling

Glasgow 1869. August heat has thickened the air and brings slum stench northwards through the streets. A growing hub of opposites, the sandstone seams of lavish villas and squalid tenements threaten to burst with a consistent flow of new inhabitants; tobacco lords and scrap workers, mill girls and merchant wives. In one of the many houses there is a group of people. They sit silently within a dimly lit room, the curtains drawn and covered by more thick swathes of material to hush dockyard clangs and shouts. They are waiting, but for whom?

A cold current ripples through the room and one of the figures, a man of broad forehead, suddenly starts, pitching forward in an attitude of reverence. The others lean in eagerly, impatiently watching the hunched figure until the head slowly raises. His blue eyes gaze upwards as he addresses the ceiling with a salute, “My greeting unto you.”

So begins communications with Hafed— Persian magus, scholar, warrior, and celestial messenger.[1]

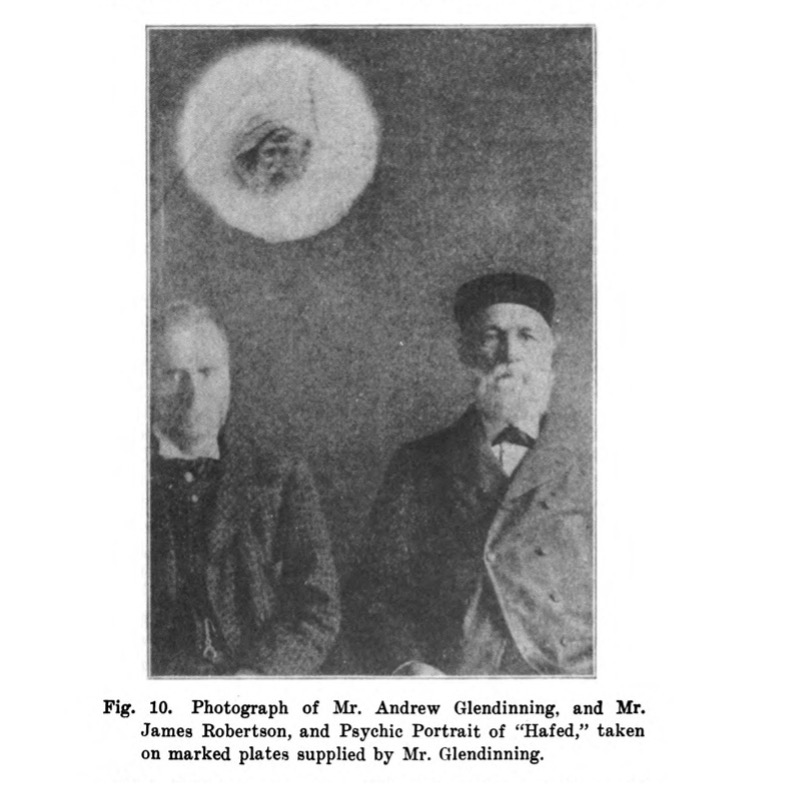

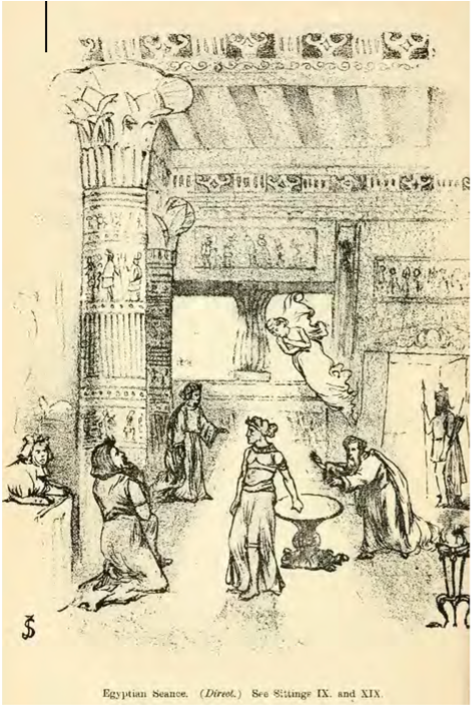

For over five years, the Glasgow spiritualist medium David Duguid channelled Hafed in multiple séances, eventually publishing the compiled narrative as Hafed, Prince of Persia in 1876. A mélange of Orientalist and apostolic influences, it recounts details of Hafed’s early life, family, and sovereignty through sittings rather than chapters. By the sixth there is decisive turn of plot when his family are murdered. In an act of transformation, Hafed puts aside warfare to follow the advice of his spirit guide. This eventually leads him to adopt a key role within the testament narrative; biblical magus, teacher of Jesus, and proselytiser of Christianity. Consistently leaving behind a wake of converts, Hafed’s actions in this didactic narrative becomes easy to anticipate. Nonetheless, as Simone Natale notes, the book went into numerous reprints and was eagerly taken up by the spiritualist press, being reviewed in journals such as The Medium & Daybreak and The Banner of Light.[2] No doubt there were many reasons for Hafed’s appeal, and one may have included its use of orientalist motifs to reflect contemporary British society, and the role of Scots within it.

Only recently have scholars started to pay attention to works such as Hafed. Most existing scholarship on Spiritualism in Britain has focussed exclusively on the English context, with little research undertaken on Scottish texts such as Hafed. When I had the opportunity to undertake a Carnegie Trust Undergraduate Vacation Scholarship, it was this academic gap, close to my own heart and heritage, that I wished to fill.

I was a girl who went through the witch phase. A phenomenon now largely accepted as something most teen girls ‘just go through’, I can testify that when as a girl broaching adolescence and still reliant on my parents, the idea of being able to fly out into the night and draw power from cosmic forces certainly has its own unique appeal.[3] Tarot cards, spirit animals, candle magick, channelling, chakras and crystals; the plethora of occult activities filled the awkward in-between time that is childhood to adolescence. Most girls end up growing out of it; boys become more interesting than broomsticks, tequila slammers preferable to tarot. My witch phase on the other hand, grew with me. Entering student life, past interests informed the new, and I began to investigate the cultural and historical origins of occult practise. This growing fascination soon bloomed into an academic pursuit, with my degree in Scottish literature tending towards the discovery of relationships between folklore, alternative spirituality, gender, and literature.

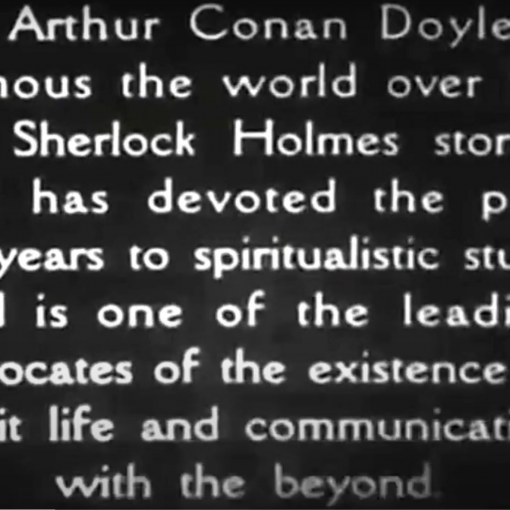

An interest in occult history remains a latent layer to my university studies. With the Carnegie Trust’s Undergraduate Vacation Scholarship scheme I finally had the opportunity to fully combine these passions with my academic studies. For ten weeks I have been researching how Spiritualism was practiced and received in Scotland at the end of the nineteenth century, specifically, how on Scottish spiritualists represented and identified with the East in various forms of writing. Supervised by Christine Ferguson, I narrowed my study to two spiritualist literary works from late-Victorian Scotland: The Mystery of Cloomber(1888) by Arthur Conan Doyle and the aforementioned Hafed, Prince of Persia (1876) by David Duguid.

Honestly, my research has conjured more questions than answered them, and I am left with a paradoxical conclusion. While Doyle and Duguid challenge notions of Western superiority, they remain reliant on Orientalist stereotype. Orientalism therefore remains pervasive, yet the Victorian spiritualists show desire to connect with the Far East.[4] Each approach is different, but the key detail is that they viewed such a connection as advantageous. In this respect, the Scottish texts challenge the ideologies of division that mark Orientalism.

Scarlett McQuillan is a student at Stirling University pursuing a BA in English Studies. Now entering her fourth year, she has spent the last summer undertaking research as part of the Carnegie Trust’s ‘Vacation Scholarship’ program. She is fascinated in the occult, folktales, gothic, Scottish landscapes and cultural storytelling. Scarlett aims to develop these interests through a master’s degree, followed by a career in academic research.

[1] This description is based upon the true historic event recorded by Hay Nisbet, publisher and transcriber of Hafed. David, Duguid. Hafed Prince Of Persia: His Experiences In Earth-Life And Spirit-Life, Being Spirit Communications Received Through Mr David Duguid, The Glasgow Trance-Painting Medium. 2nd ed. Glasgow: H. Nisbet, 1876. IAPSOP.

[2] Reviews can be found in various editions of the following periodicals: The Spiritual Magazine, The Medium and Daybreak, The Two Worlds, St. James Magazine (quoted verbatim in The Medium and Daybreak), Glasgow Christian News, The Banner of Light.Simone Natale, Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture, Pennsylvania State University Press: Pennsylvania, 2016, 124.

[3] Peg Aloi and Hannan E. Johnston, eds. The New Generation Witches: Teenage Witchcraft in Contemporary Culture, London: Routledge, 2007.